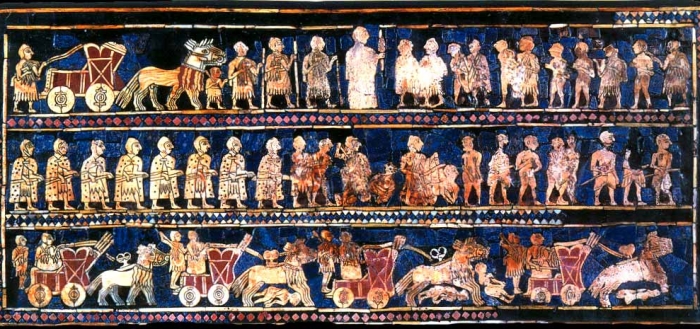

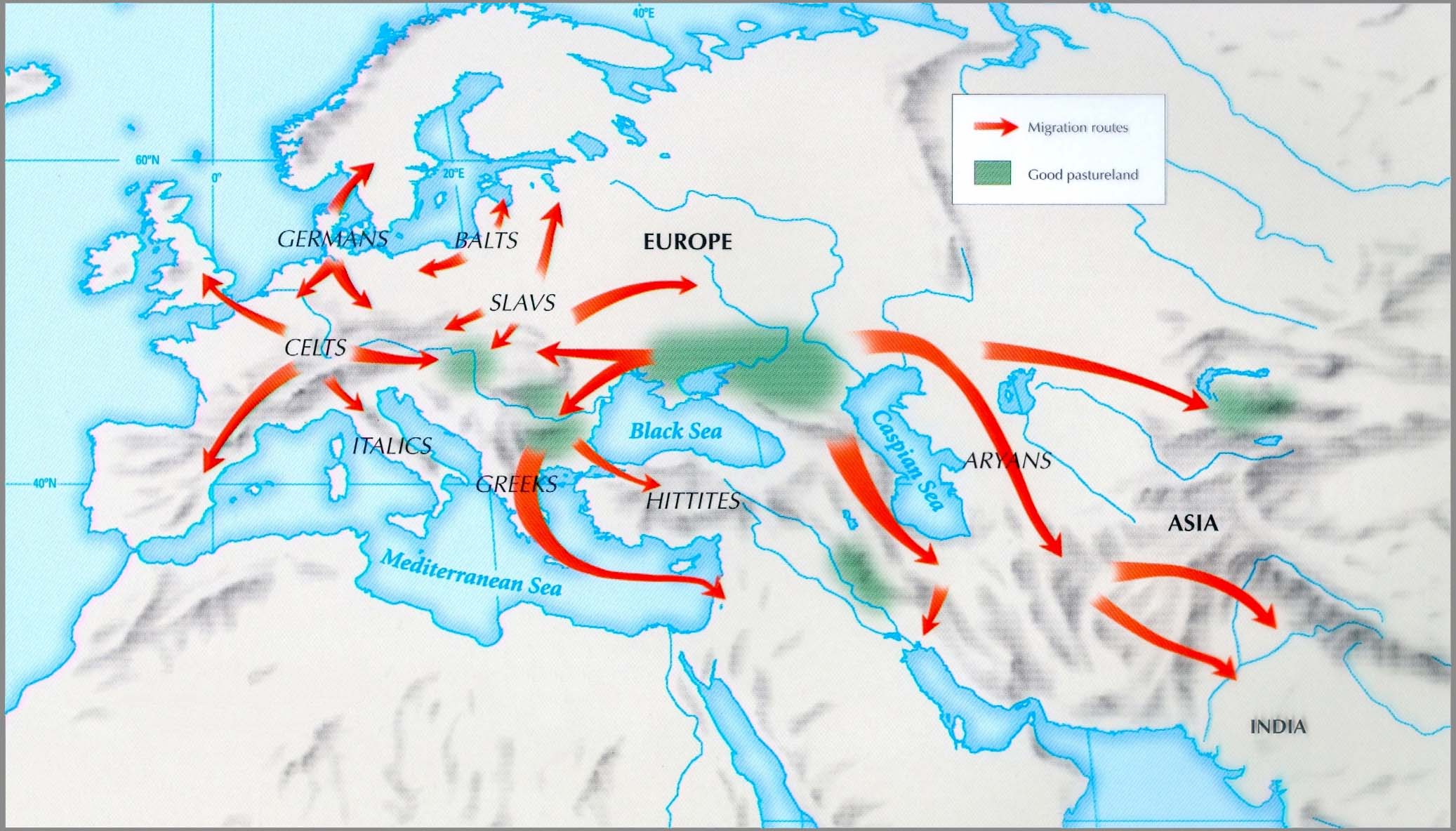

Throughout the Western world, European civilization has dominated the naming customs ever since the Ancient times. Greek names were en vogue during the Hellenistic period, Roman names in late Antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages, when the now modern Romance or Slavic languages were created, which in turn left their own clear print upon names.

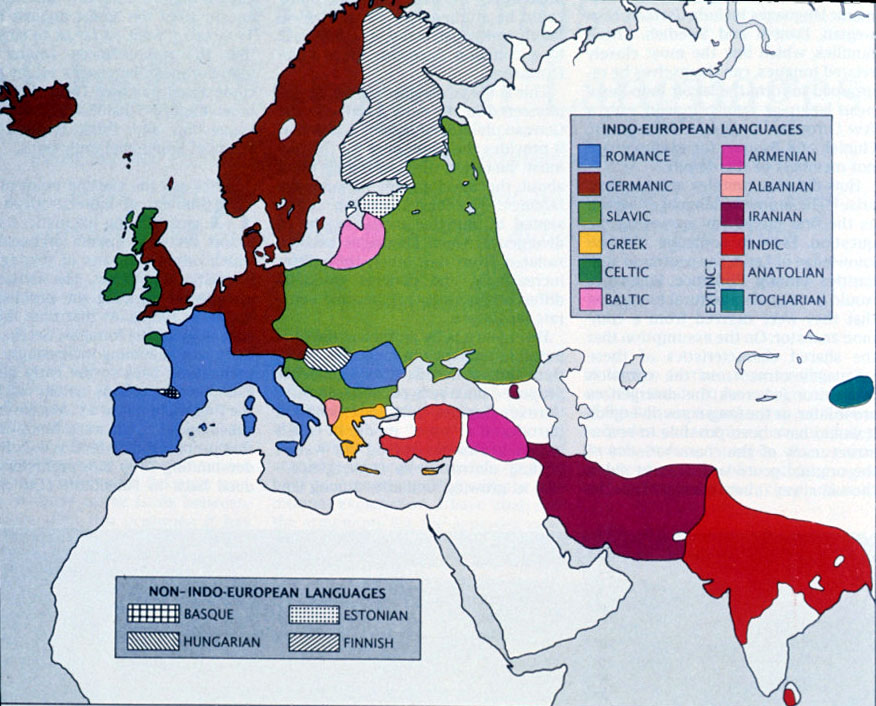

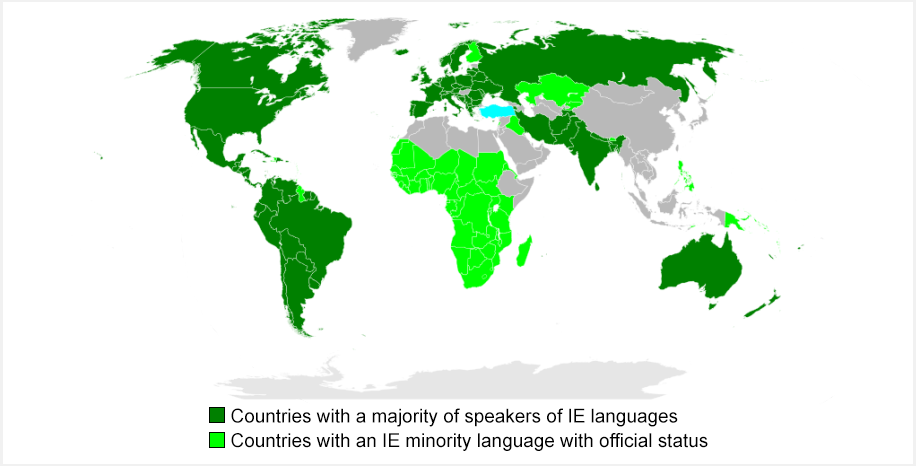

The Indo-European languages today

French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian are all Romance languages and all trace their roots to classical Latin.

Russian, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian, Serbian, Croatian, Ukrainian are, among others, languages based on Old Church Slavonic.

Greece has never given up on its traditional names and neither did Albanian, a very old language in its own right.

The Germanic languages or Saxon, as they have sometimes been called, which include German, English, Norwegian, Swedish, Icelandic, Danish and Dutch, have also set the trend in naming customs since the Middle Ages and at times have also borrowed Latin ones.

The Baltic Lithuanian and Latvian are a separate group, as ancient as Greek and as thorough in their following of local traditions.

What’s left of the once widespread Celtic languages, mostly Irish and Gaelic, have also tried to hold on to their identity by the use of names.

All the languages mentioned above have in common their Indo-European root, as they are all part of the Indo-European, Sanskrit related linguistic group.

Further to the East we find Armenian and Persian, Indo-European as well but evolving quite differently over time.

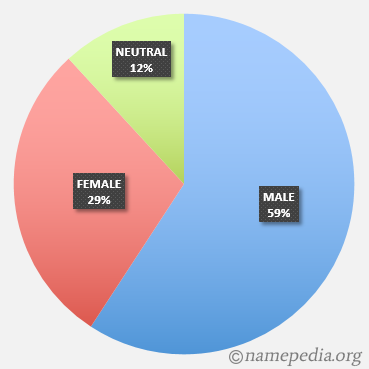

How gender is created

When we take a look at the majority of names used in Europe ever since the Indo-European migrations during the Bronze Ages, we find that female names tend to end in “a”, whether they are older or modern. We have English female names ending in “a”, French, Italian, Spanish, Romanian, all the Slavic ones, Greek, Baltic and even some of the Germanic ones.

Another common female ending is in “e”, as noticed in Albanian, German, Dutch and sporadically in some other Indo-European languages.

There have been various speculations as to why this is so, mostly involving Sanskrit as original common language and tracing parallels with classical Hindi, Bengali or Punjabi.

This article argues another theory and while it is not scientifically exhaustive, it will follow its arguments language by language.

The reason for the “a” ending may not be found in Sanskrit or even so far back as a common, recreated Proto-Indo-European language. We suggest a far more accessible, yet meticulous theory, based on the way Indo-European languages create gender. This is not merely proper noun gender but common noun grammatical gender, used for the entire lexicon.

Nouns in any language are divided between common and proper, all names belonging to the latter. Thus, names are no different from any other noun, from a grammatical point of view, thus they are obliged to follow the general rules existent in the language. Their declinations, genders, multiplication and transformation are all closely linked to the evolution of the language itself.

Creating gender in proper nouns or names is no different from creating gender in common nouns, since grammatically they are viewed as the same word class. This is why we consider that gender use in nouns reflects on the gender use in names.

From female nouns to female names

On a piece by piece analysis, we will show that the female grammatical gender in most Indo-European languages is created using an “a” or an “e” ending. That which was in use in their older form and linguistic branch came to be the norm in their modern counterparts as well. This means that if Old Church Slavonic or Latin made the female gender using an “a” ending, today’s Slavic and Romance languages will do the same.

First we have to identify the main branches of the Indo-European linguistic family and see their trends in gender making. Most Indo-European languages have grammatical noun gender, the main exceptions being Armenian, Persian, which have very few female names ending in “a” and English, which has lost its gender but has taken to using many Latin names.

From a glance we can distinguish several branches of the Indo-European language family of the Bronze Age migration: Latin, Greek, Baltic, Thracian (extinct) and Illyrian, the Germanic one, the Slavic one and the Celtic one, all of which have left their mark upon European civilisation.

Latin

Classical Latin typically made a grammatical feminine gender in “a”: silva – forest and aqua – water and gave us names like Emilia and Melania.

All its Romance children: Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian and Balkan Wallachian, follow the same rule for grammatical femininity with an “a” or “e” ending. Italian via and pietra – street and stone are feminine, Spanish manzana and rosa – apple and rose are feminine, Portuguese mesa and cama – table and bed are feminine, Romanian casa and fereastra – house and window are feminine and French bouteille and lutte – bottle and fight are feminine. Due to the Germanic influence, French makes for a special case, as we shall see.

If we look at the female given names in these languages we can discover quite a similar situation: Italian Monica and Laura, Spanish Esmeralda and Soraya, Portuguese Filipa and Margarida, Romanian Ruxandra and Ileana, French Clémence and Yvonne.

Greek

The Greek branch has feminine words like petseta – towel and gramma – letter and female names like Theodora and Elektra.

Illiryan

The Illiryan line has only one modern linguistic child – Albanian, with dritare – window and tavolinë – desk and names like Fatmirë and Afërdita. The “a” ending names of this language can be either borrowed or have been influenced by the neighbouring cultures.

Slavic

A large branch and one which makes its feminine quite clearly in “a” is the Slavic one. From Old Church Slavonic to modern day Slavic languages, most common nouns ending in “a” are female and most given names ending in “a” are female, too.

There is Russian vodka and Olga, Polish żaba – frog and Małgorzata, Ukrainian zemlya – earth and Tetiana, Belarusian sviečka – candle and Oksana, Czech veverka – squirrel and Eliška, Slovakian koza – goat and Bronislava, Serbian mačka – cat and Milica, Bulgarian krava – cow and Darina, Croatian vrata – gate and Lucja, Bosnian crkva – church and Lamija and Slovenian ptica – bird and Zala.

Germanic

The Germanic branch is quite different in its grammatical structure and evolution. The languages have clear genders, but this is not directly reflected in the formation of names.

English makes for a special case, as it has lost its genders following the Norman conquest of 1066, A.D. In fact, Modern English is the result of the Norman and subsequently French influence of Old Saxon, a rather Norse type of language, marked by gender in nouns. The incoming Latin layer brought a whole new vocabulary, French and Latin inspired names, among the Old Saxon ones and a confusion in gender attribution, as the Old French noun gender did not match the Saxon one. Thus, English has lost its grammatical gender altogether, yet has retained some “a” ending female name like Samantha and Emma.

In the other Germanic languages, the female names have been Latinized by adding “e” and “a” and this is why today they resemble other European names. In the olden times, when Old Norse was a common language among Germanic and Scandinavian people, names were created by joining two affixes, which had a meaning by themselves. Typical names like Brunhilde, Kriemhilde and Hroswitha were once Brunhild, Kriemhild and Hroswith.

The placement of the affixes would determine the gender of the name. For example, if “hild” is placed at the end, the name is female, if “bert” marks the ending, the name is masculine. This does not apply after the Latinizing of names, as Roberta is definitely female. It is the same with the other Germanic languages. Danish has Elsa, Norwegian has Freya and Inga, Swedish has Bengta and Birgitta.

Dutch uses mostly “a” ending female names like Fenna and Geertruida, due to a strong Latin influence, both religious and cultural. The names that have not been influenced by Latin end in “e” like Godelieve and Veerle.

This is one of the few Indo-European sub-branches which has given us modern female given names that do not end in “a” or “e”, like Ingeborg, Ingrid, Richardis. However, when adapted to the other non-Germanic languages, these names will be given an “a” ending like in Mathilda and Hilda.

French is one of the Latin languages which has felt the strongest Germanic influence, causing it to lose the typical “a” ending of the feminine gender, keep the “e” and add some consonants as in abbaye – abbey and maison – house.

Baltic

The Baltic branch also sticks close to the “a” and “e” ending female nouns, in Lithuanian we have saulė – sun and Danguole, Latvian pilsēta – fortress and Laima.

Celtic

The Celtic linguistic branch uses both “a” and “e” endings to mark the feminine, but mostly consonants like “n”, “th”, “ch”, “d”. This has created female names like Keira, Caitlinn, Morgan, Sinead, Aoife, Riomthach. It joins the Germanic family as originator of consonant ending female names.

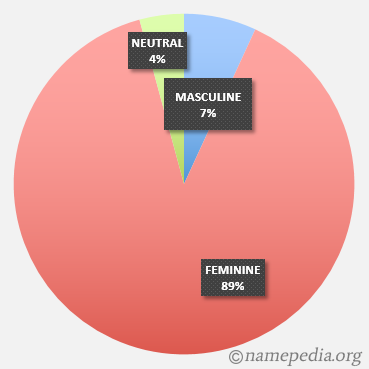

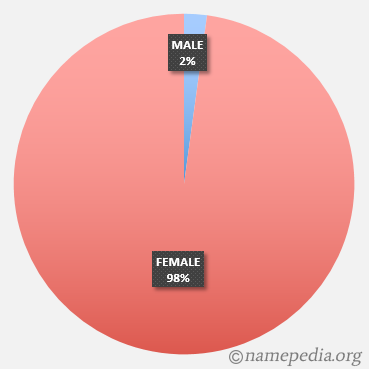

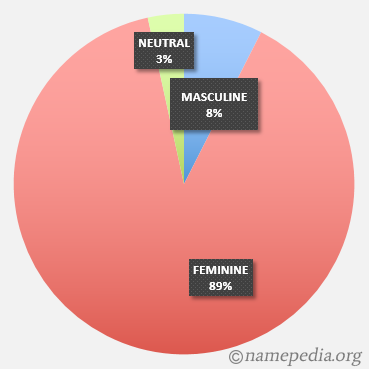

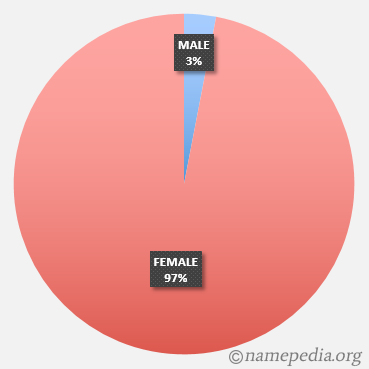

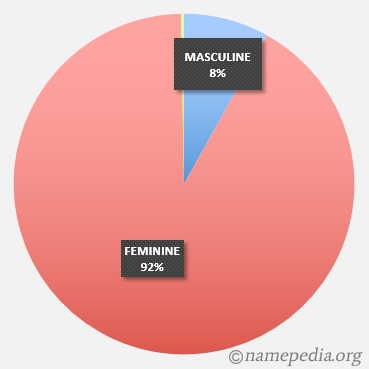

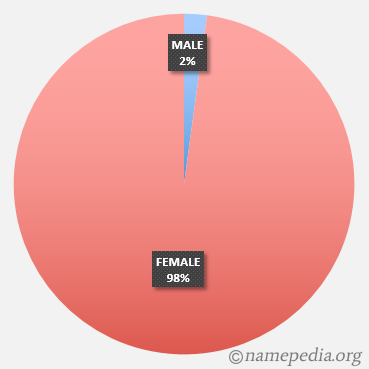

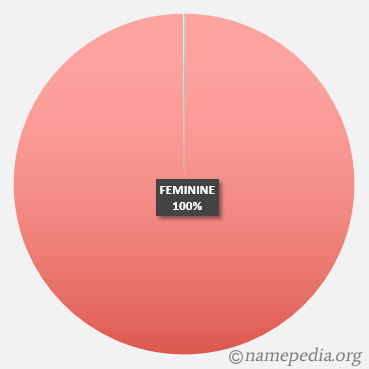

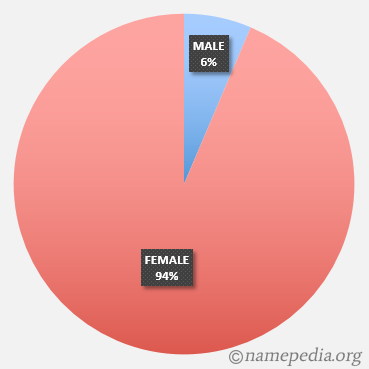

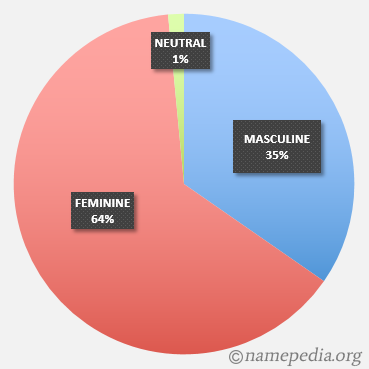

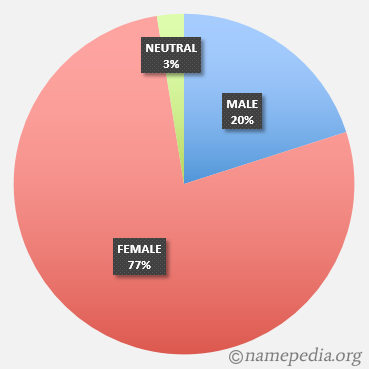

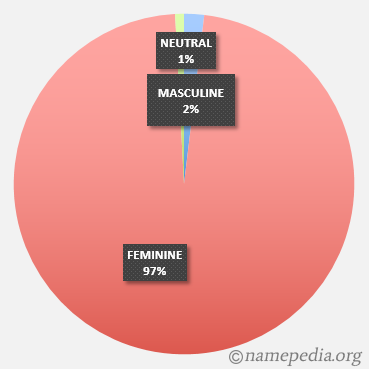

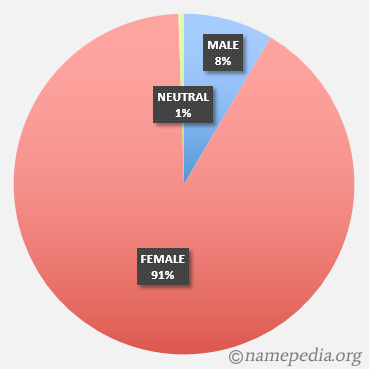

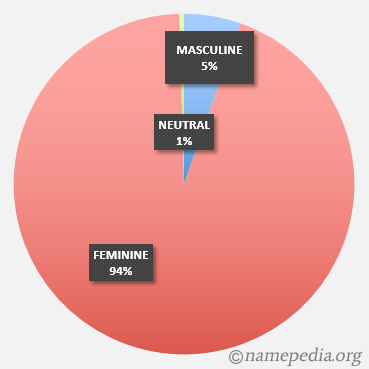

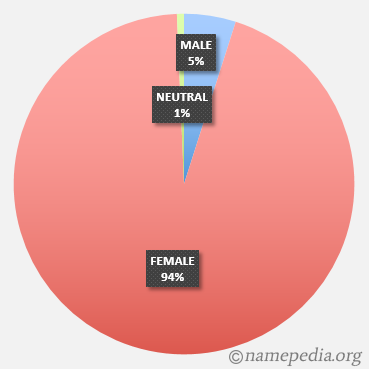

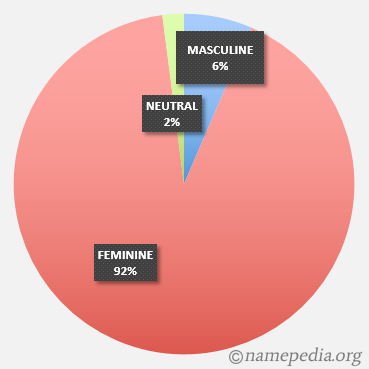

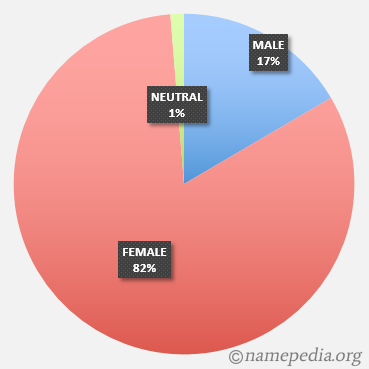

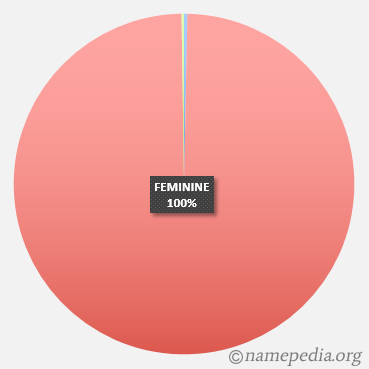

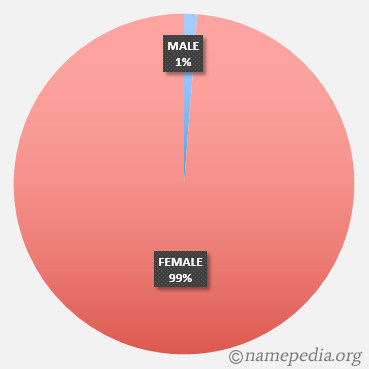

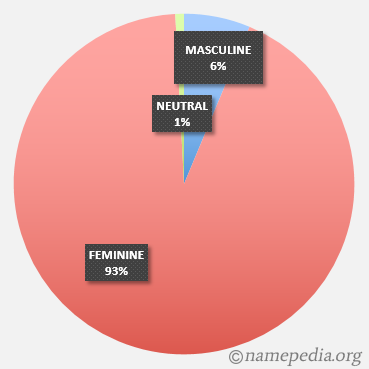

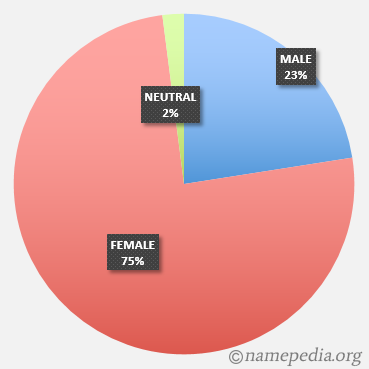

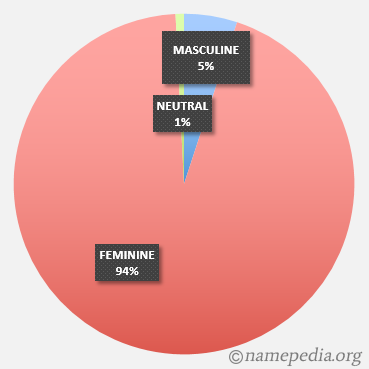

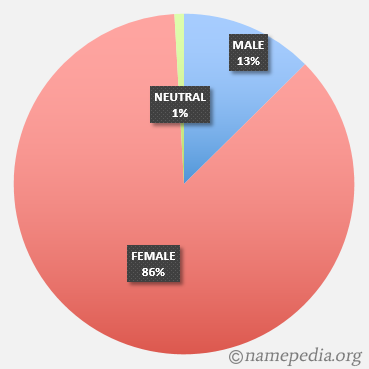

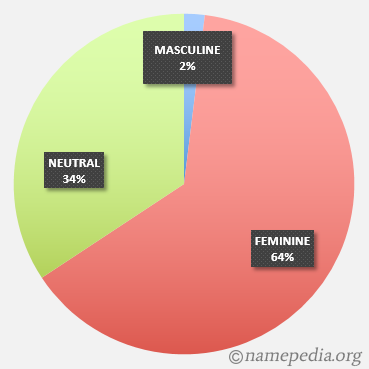

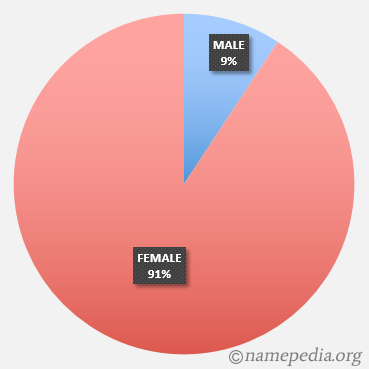

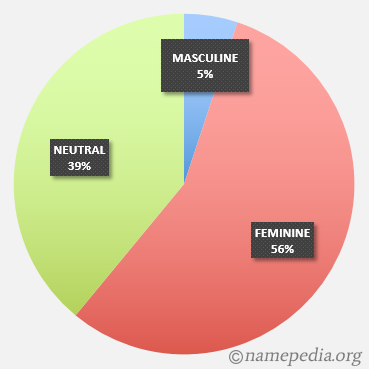

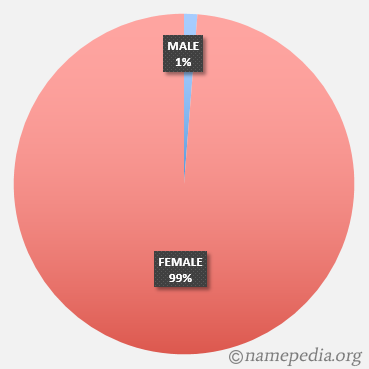

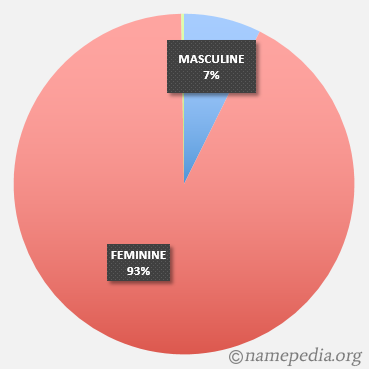

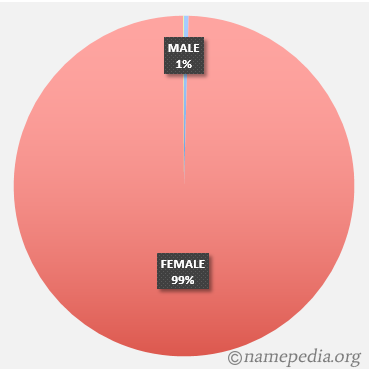

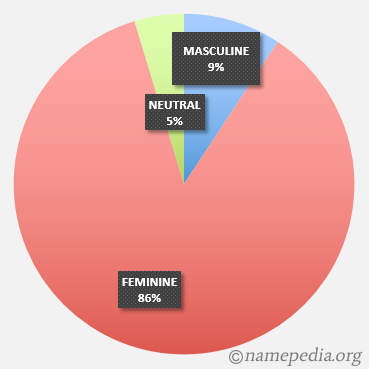

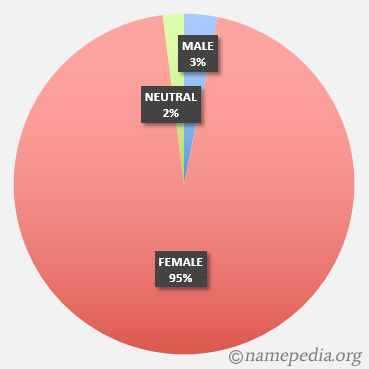

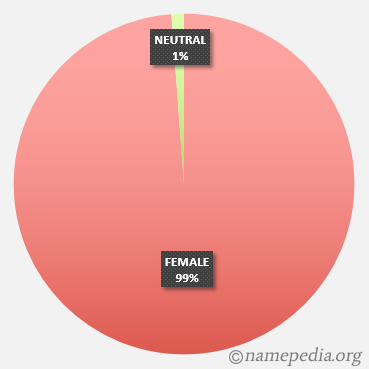

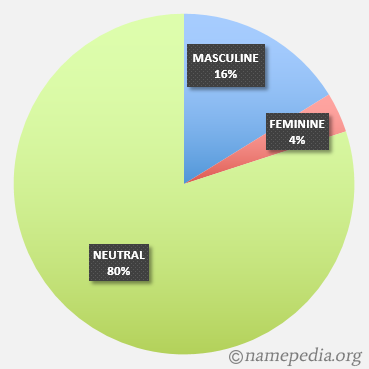

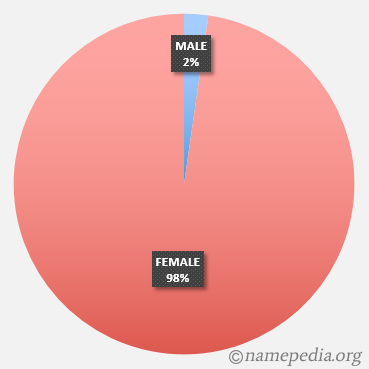

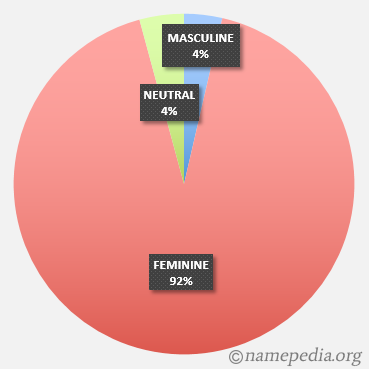

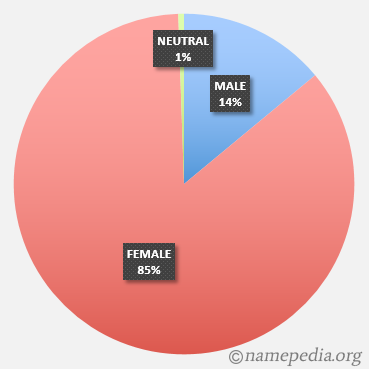

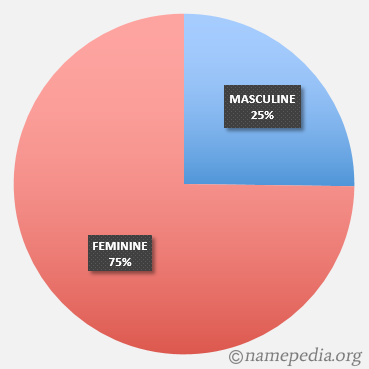

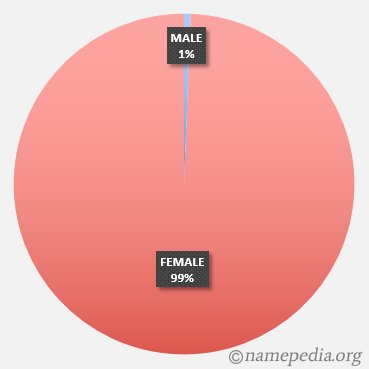

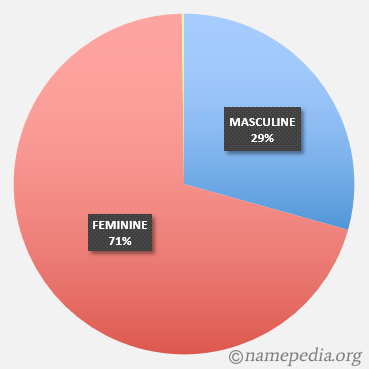

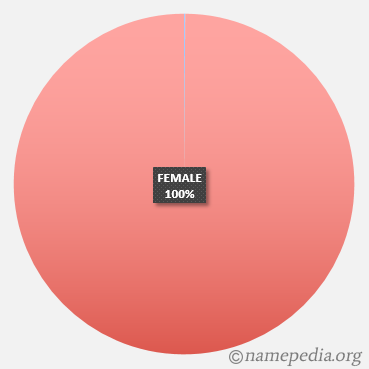

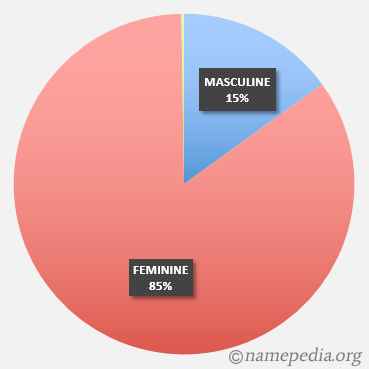

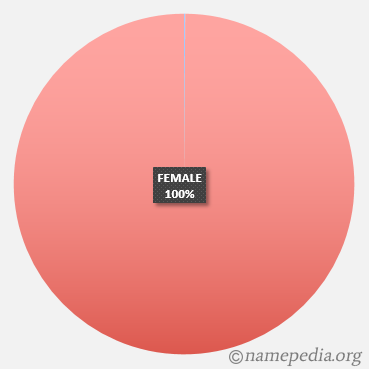

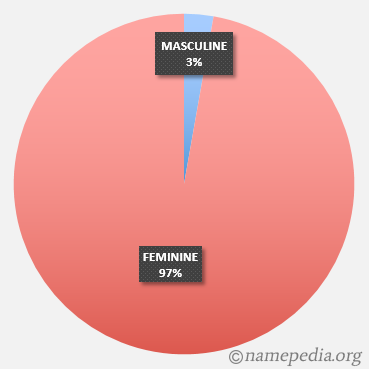

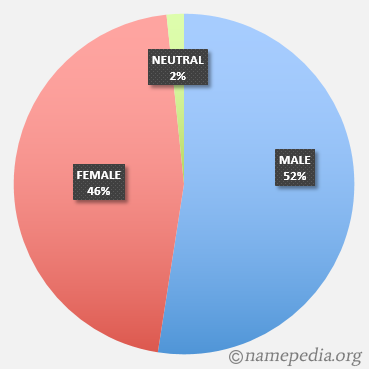

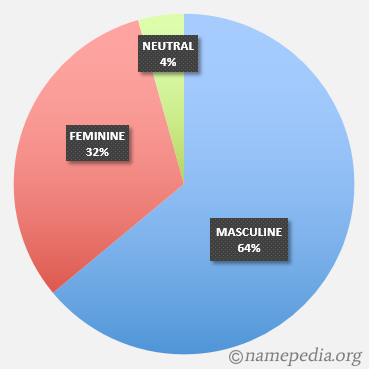

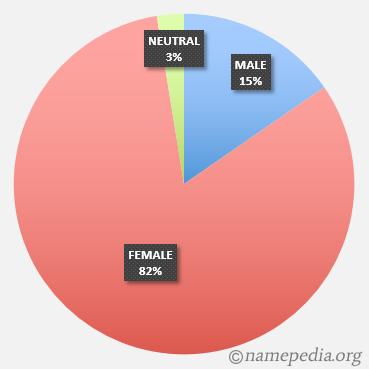

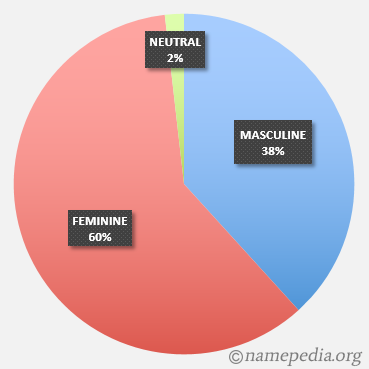

The following charts show language by language how gender use in common nouns reflects on the gender use in names.

Feminine: 4453 (89%)

Neutral: 211 (4%)

*Includes nouns ending in a and á.

Feminine: 2230 (92%)

Neutral: 7 (0%)

*Includes nouns ending in a, á and ã.

Feminine: 1377 (100%)

Neutral: 1 (0%)

*Includes nouns ending in a and ă.

Feminine: 4863 (97%)

Neutral: 42 (1%)

*Includes nouns ending in а and я.

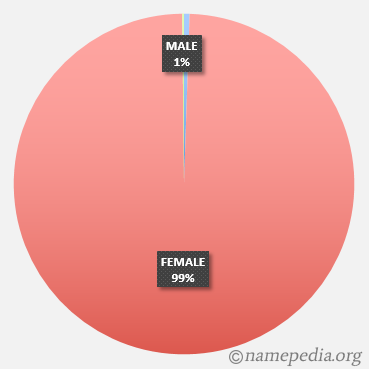

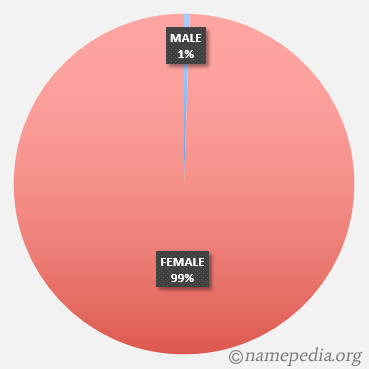

Female: 685 (91%)

Neutral: 4 (1%)

*Includes names ending in а and я.

Feminine: 2515 (92%)

Neutral: 56 (2%)

*Includes nouns ending in a and á.

Feminine: 6543 (100%)

Neutral: 15 (0%)

*Includes nouns ending in а and я.

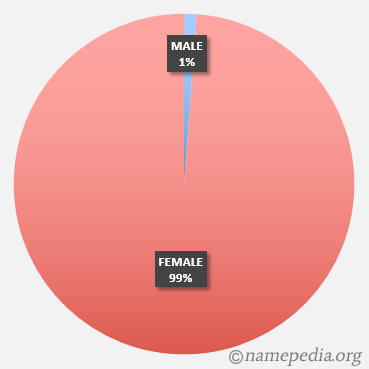

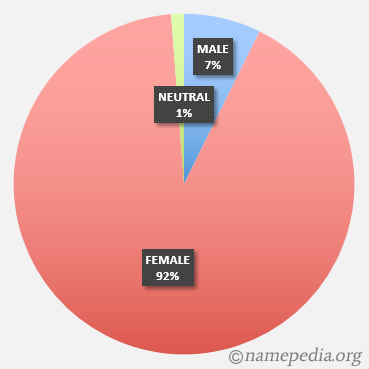

Female: 2127 (99%)

Neutral: 5 (0%)

*Includes names ending in а and я.

Neutral: 8 (1%)

*Nouns don’t have feminine and masculine gender except for a few words.

Feminine: 1152 (99%)

*Includes names ending in a and å.

**Nouns don’t have feminine and masculine gender.

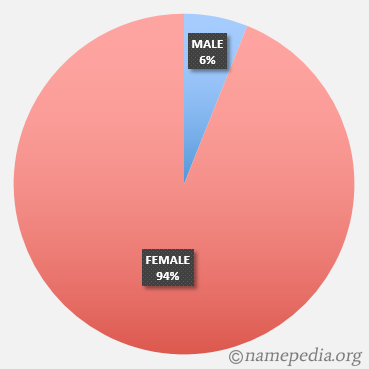

Feminine: 62 (94%)

*Nouns don’t have feminine and masculine gender.

Feminine: 273 (75%)

*Includes nouns ending in e, ę and ė.

Feminine: 314 (71%)

Neutral: 1 (0%)

*Includes nouns ending in e, ę and ė.

Feminine: 338 (85%)

Neutral: 1 (0%)

*Includes nouns ending in a and ā.

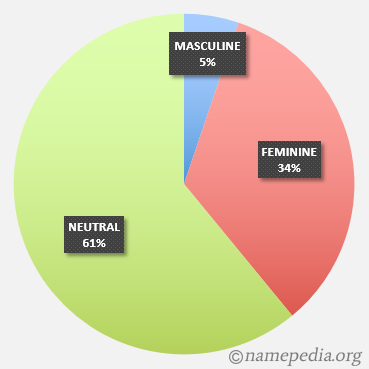

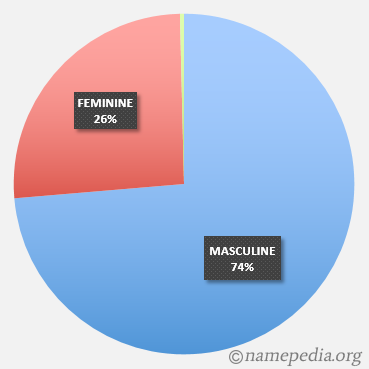

Feminine: 68 (26%)

Neutral: 1 (0%)

*Includes nouns ending in a and á.

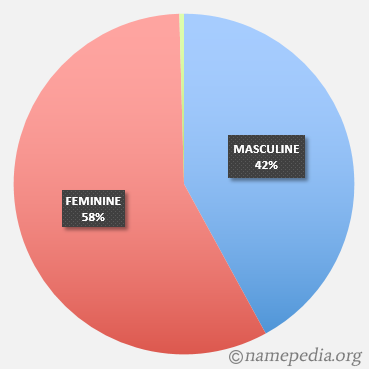

Feminine: 130 (58%)

Neutral: 1 (0%)

*Includes nouns ending in e and é.

Feminine: 51 (32%)

Neutral: 7 (4%)

*Includes nouns ending in a and à.

Feminine: 166 (60%)

Neutral: 5 (2%)

*Includes nouns ending in e and è.

A synthetic overview

On a wider scale, we can identify about three lines of development for grammatical gender in the Indo-European linguistic family:

- one that makes the feminine in “a” and “e”, which includes Latin languages, Slavic, Baltic and Greek,

- one that still uses “a” and “e” but adds consonant groups as well, like Germanic, Illyrian and Celtic,

- and one which loses gender differentiation altogether, with Armenian, Persian and English.

This doesn’t mean that the languages belonging to a particular line are indeed closely related. In fact, if we would consider grammatical similarities, as well as synthetic vs. analytic language division, we would find that Germanic and Slavic languages have more similarities in terms of language structure than Germanic and Latin, yet regarding gender development, Latin is closer to Slavic, Greek and ancient Illyrian. Celtic languages share similarities in terms of gender formation with Germanic ones, but we have to take into account the geographical area of linguistic distribution.

The Eastern Indo-European languages Armenian and Persian have been subjected to different influences over time and have developed in other directions than their Western relatives. This is also the reason why they do not have any genders and do not mark their female names with an “a” or “e”.

Most of Europe seems to have been dominated by the Bronze Age branch, the Southern part by Latin, Greek, Thracian (now extinct) and Illyrian, while the Northern part by the Celtic, Germanic branch. Equally old is the Baltic family, closer to Latin than to Germanic and the later arrived Slavic group. This last one shares characteristics with Latin, Greek and Germanic as well.

The Indo-Europeans have arrived in Europe from their homeland by two ways, as the newest research suggests: predominantly through the North of the Black Sea and through Anatolia, which would explain the existence of Persian, Armenian, the now extinct Anatolian (of which Hittite might have been a part of) and Tocharian languages.

Conclusions

If we are to speculate upon language migration we can distinguish two main directions of movement in Europe: to the north and to the south. We can also notice some similarities between the languages that have settled north wise or south wise in terms of gender creation. As their basic grammatical common structures of today suggest, at some point either before their arrival in Europe or perhaps just after their migration, they might have split into two main groups.

This partition is only based on the formation of female gender and it does not regard other linguistic characteristics.

Modern Europe is dominated by the Indo-European civilisation, and after Colonialism and the spread of Christianity, other parts of the world have adopted its names. As most Indo-European languages which have a gender division in nouns create the feminine using an “a” or “e” ending, so most female given names will also end in “a” or “e”.

This probably reflects an earlier view on grammatical femininity, as it must have existed in Proto-Indo-European and which could also be linked to Sanskrit gender characteristics. Sanskrit alone cannot be used to explain the structure of modern names, but plays an important part in linguistic archaeology.

A far simpler and clearer answer lies within the grammar we speak daily, shaping our view of the world and of feminine identity.

Data sources:

• For the given name charts: http://namepedia.org

• For the noun charts: https://www.wiktionary.org

Photo sources:

• Standard of Ur: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_of_Ur

• Indo-European Languages map: http://www.usu.edu/markdamen/1320Hist&Civ/chapters/07IE.htm

• Indo-European Migrations: http://teachersites.schoolworld.com/webpages/GHurst/files/scan0003.jpg

• Speakers of Indo-European Languages: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_languages

I have gathered a good list of girl names ending with -a