In most of the Indo-European languages that have gender in nouns, we notice that personal names also follow specific gender rules.

In the previous article “Why most European names ending in A are female“, I tried to analyse and explain why so many European female names today end in “a”. Following the structures of all of the Indo-European languages, we have observed how grammatical gender is projected unto proper name creation. This explained the constant presence of the “a” sound.

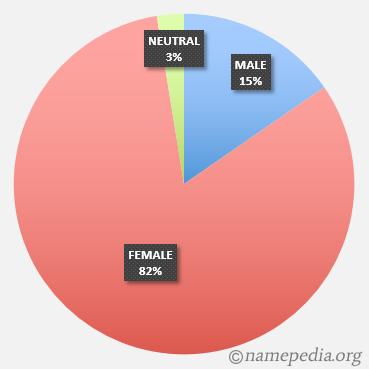

However, there are also male names that end in “a” in most Indo-European languages, which seem to go against linguistic rules. In this article, I will try to analyse and explain the existence of “a” ending male proper names in Indo-European languages.

Names and their Origins

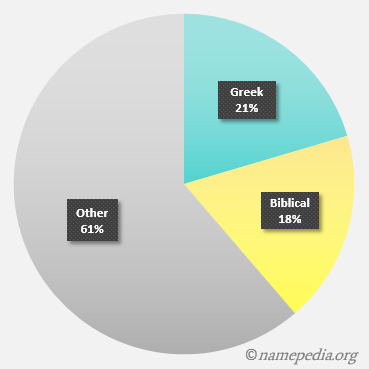

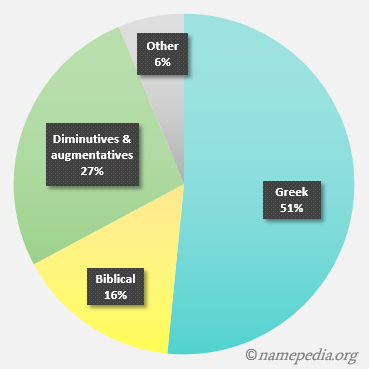

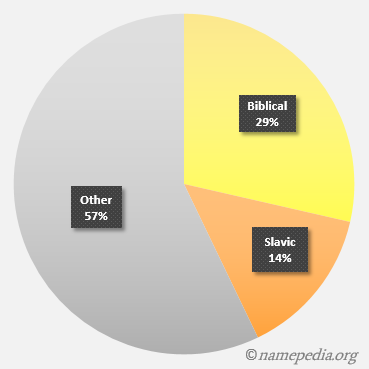

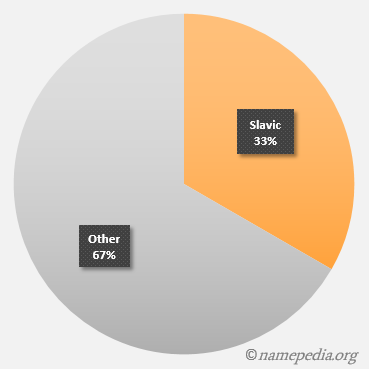

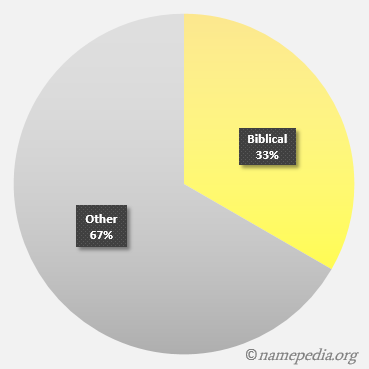

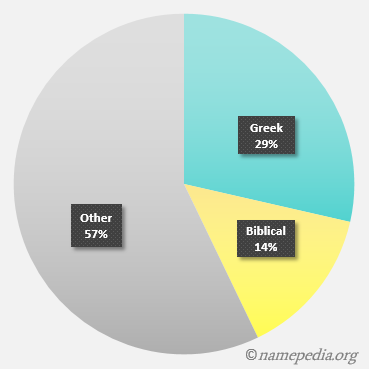

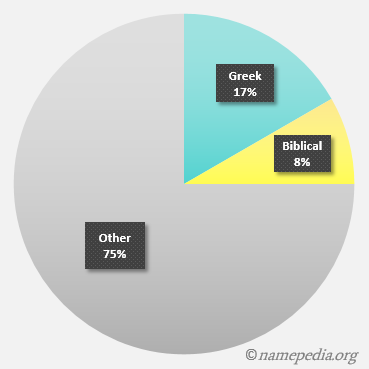

The first step of our analysis is to determine the origin of the names and see their initial form and ending. Some names appear in all languages, as they are religion-based or have been borrowed from one culture to another. The religious names are either Biblical and originally Hebrew, or come from saint names in Greek or Latin.

Many male names of Slavic origin, existing in Slavic languages or borrowed from them end in “a”.

Some Indo-European languages have borrowed names from non-Indo-European sources, either because they were geographically close to those cultures or because they came into contact with them through trade or travelling. In this case, the names were not analysed as the others, since they come from fundamentally different linguistic backgrounds.

Religious and ancient names

In the case of religious names, we notice different linguistic phenomena occurring, depending on the language. The Bible based, Hebrew names that end in ‘a’, like Elja and Eremia, did not originally end in a vowel.

Hebrew is a consonantal script, which means that it only writes down the consonants (or perceived consonants) of a word. Originally, all Hebrew names that seem to have ended in “a”, actually ended in “ה” (He), which sounds like an “a”, for instance, יִרְמְיָה transcribed as Jeremia. When the names started being used in other languages, they were adapted and spelled phonetically.

A similar phenomenon happens with classical Latin and Greek names. Latin names either initially ended in “us” or they were not a given name or praenomen, but were developed from adjectives and were used as cognomen or nickname.

Romance languages today use names like Seneca or Numa as given names, yet these were originally cognomens. Some Italian and Portuguese names have been created through the same process as Latin cognomens, from adjectives or nicknames, eventually ending in “a”. Typical names like Bonaventura or Boaventura and Boninsegna are simply types of cognomens.

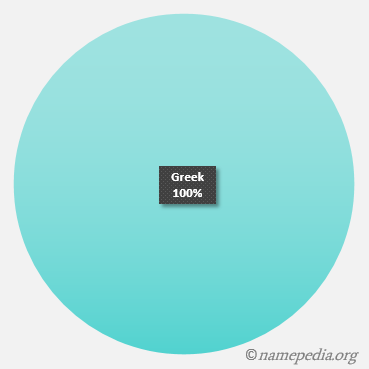

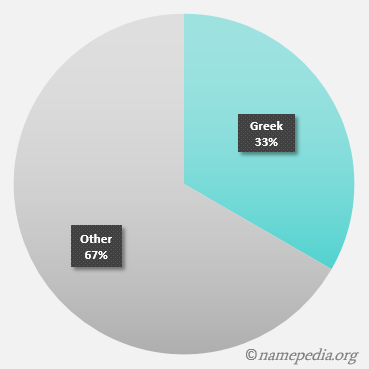

Greek origin names are even simpler to explain, since Greek names that end in “s” are male. So when they were borrowed, again due to phonetic reasons, they’ve lost this ending. If we look at the number of modern Greek male names ending in “a”, we notice that the very few existing ones are not Greek in origin. Names like Thomas and Nikitas became Toma and Nikita.

In the case of Slavic names, we observe two linguistic phenomena. One of them resembles the Latin cognomen, that is, names derived as nicknames through a genitive. The genitive singular male declination in Slavic languages is always in “a”. Thus we get names like Przezdoma or Niegodoma, meaning homeless.

The other linguistic phenomenon, which is applicable to the large number of male names ending in “a”, is related to the Old Church Slavonic Cyrillic.

In Old Church Slavonic, male nouns and male names ended in “ъ”, a closed back unrounded vowel, which today only exists as a mute sign in Russian, as the letter “ă” in Romanian and ” Ъ” in Bulgarian. The Slavic masculine common nouns that end in a consonant today, used to end in “ъ” in Old Church Slavonic, as did male names. The names were later transformed and started ending in “a”, which is how we know them today. Кирилъ became either Kiril in Russian or Chirilă in Romanian.

Names that were once something else

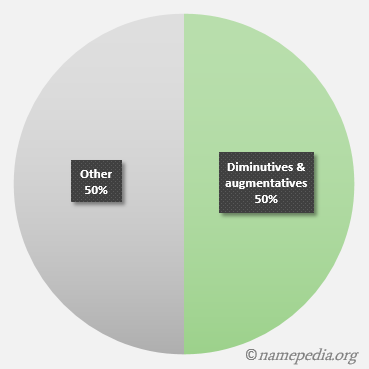

In all of the Indo-European names we find many that were once a diminutive or a short form, but have come to be used as given names over time. If the diminutive or short form was made using a vowel, then we ended up with a male given name ending in a vowel, like the Spanish short Gonza from Gonzalo.

A great number of the “a” ending male names are diminutives, especially in Romanian and Slavic languages. They follow different grammatical rules and must be analysed separately.

Most names that come from diminutive forms are found in the Slavic languages and Romanian, the only Romance language that has suffered a Slavic influence. The sound “ă” comes from Slavonic, as well as the diminutive ending “-iță“, such as Gheorghiță.

Slavic phonetics, thus the Cyrillic alphabet too, has a special feature that becomes quite important when considering diminutives. In the Slavic phonetic system, the sound “ya” is perceived as one phoneme and written down by one letter – Я, which marks the ending of many diminutives, Dimitry becomes Mitya. Hence, for a non-Slavic listener, they might sound as if they end in “a”.

Another feature of Slavic name diminutives is that they are not gender distinctive. Unlike the diminutive suffixes that apply to common nouns, which are quite clearly male (-ik, -ok, -yok, -chk-, -shk-, -on’k-, -en’k), female (-chka, -shka) or neutral (-shko), the ones that apply to names are the same for all genders. This is why the name versions resulted can end in a vowel, from Aleksey you get Alyosha.

Detailed situation of the name situation by language (just for private use):

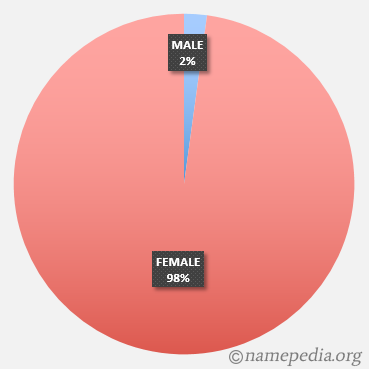

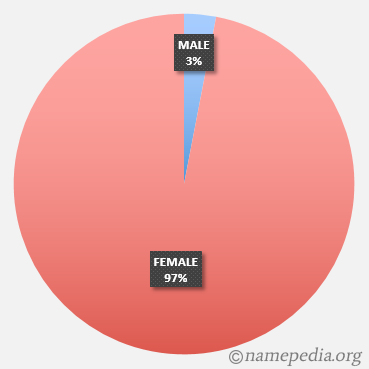

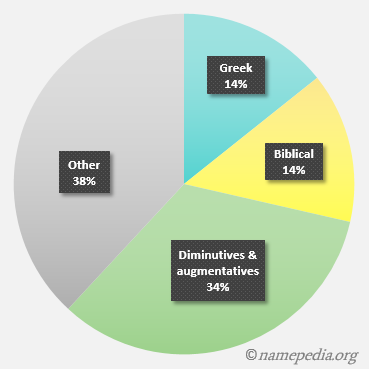

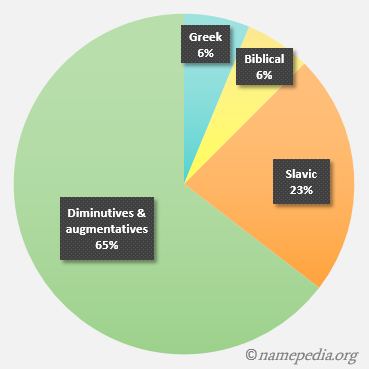

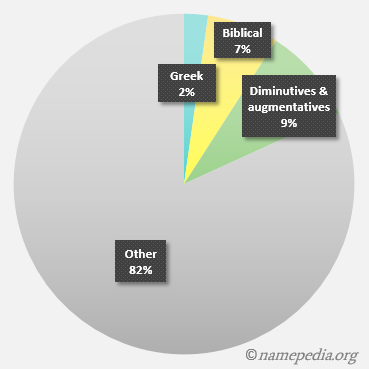

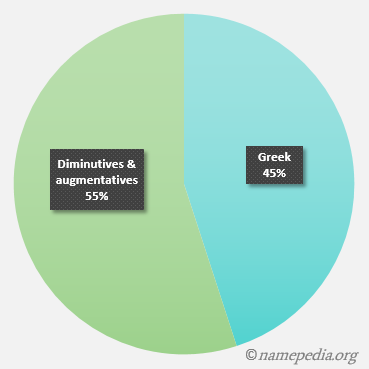

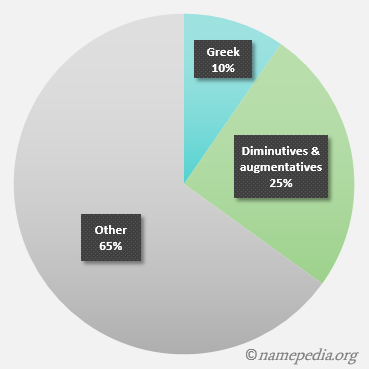

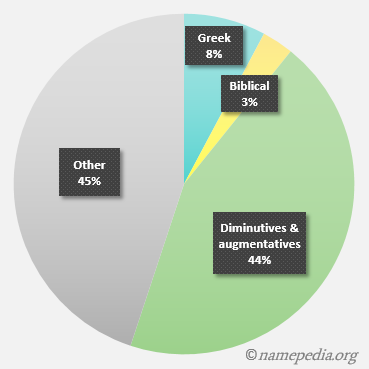

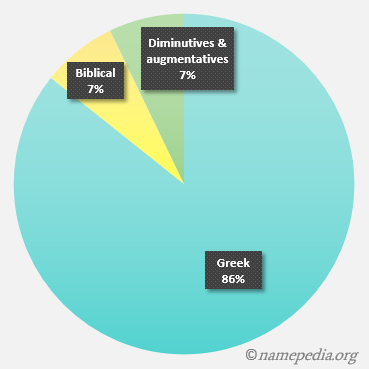

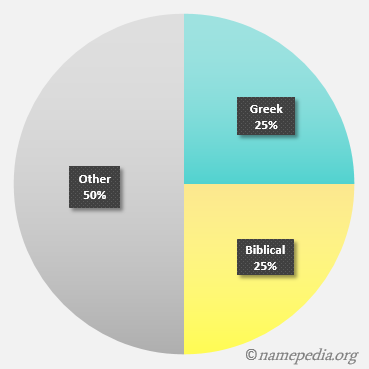

Biblical: 3

Diminutives and augumentatives: 7

Other: 8

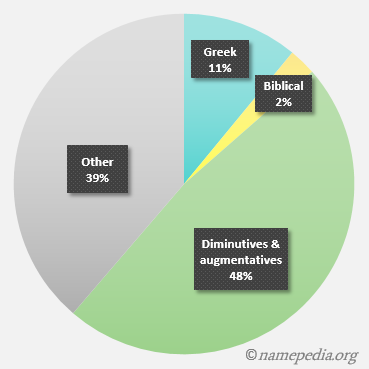

Biblical: 6

Slavic: 22

Diminutives and augumentatives: 62

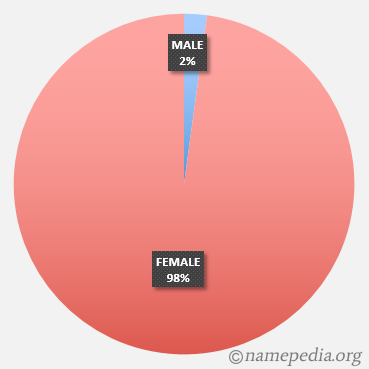

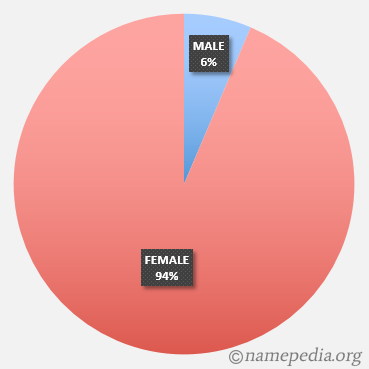

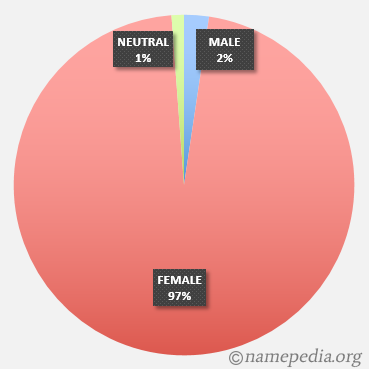

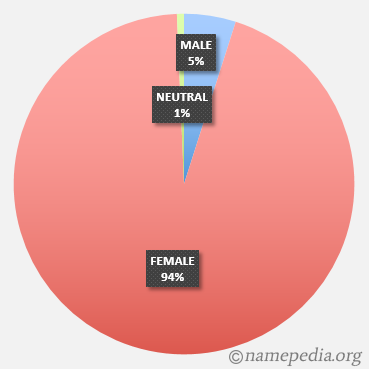

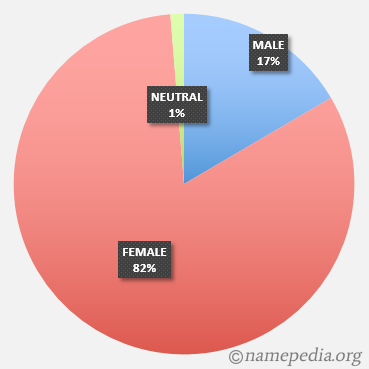

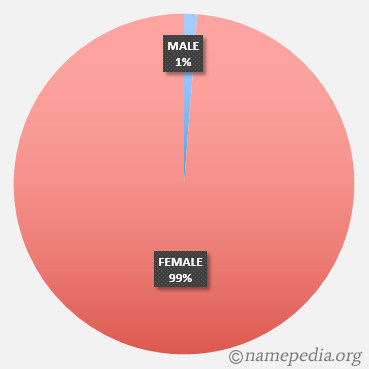

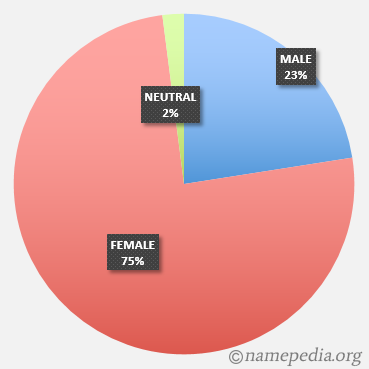

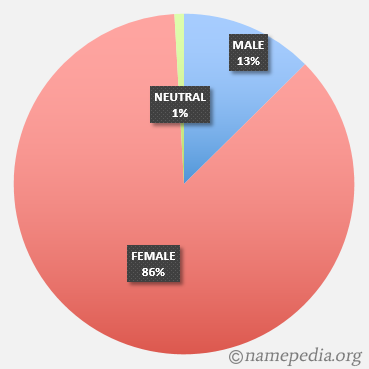

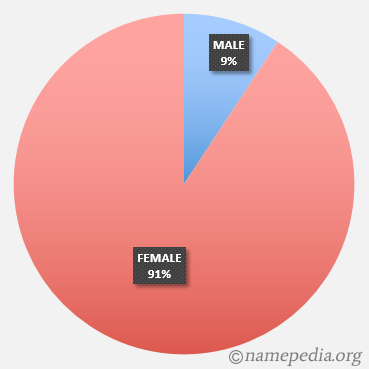

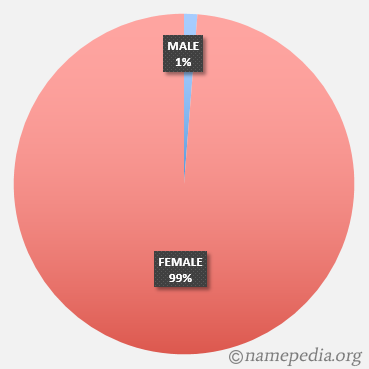

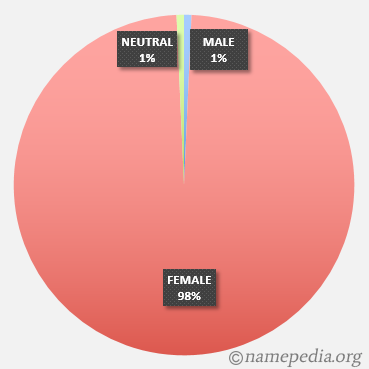

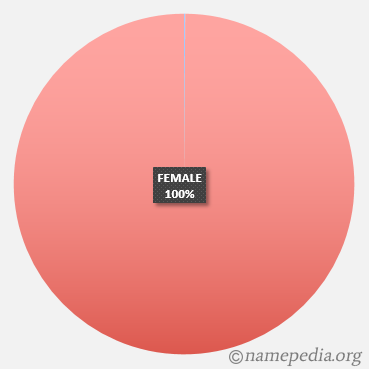

Female: 685 (91%)

Neutral: 4 (1%)

*Includes names ending in а and я.

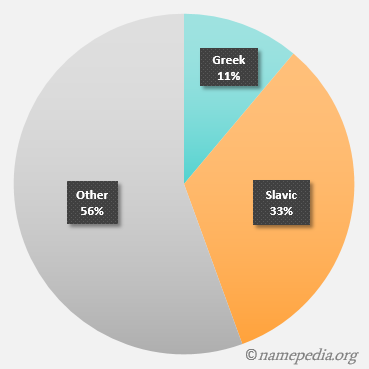

Biblical: 10

Diminutives and augumentatives: 17

Other: 4

Biblical: 3

Diminutives and augumentatives: 4

Other: 36

Biblical: 4

Diminutives and augumentatives: 74

Other: 60

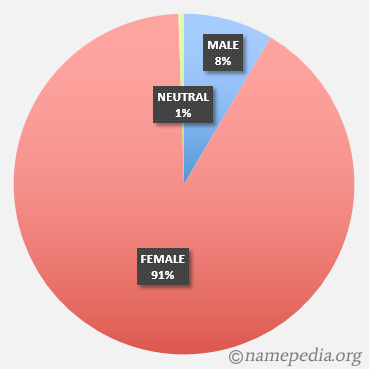

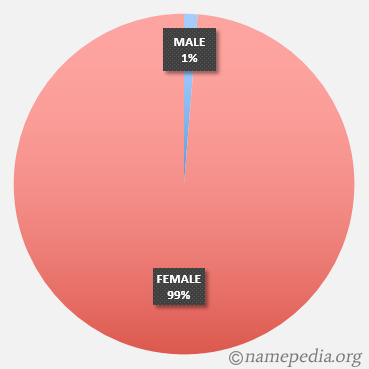

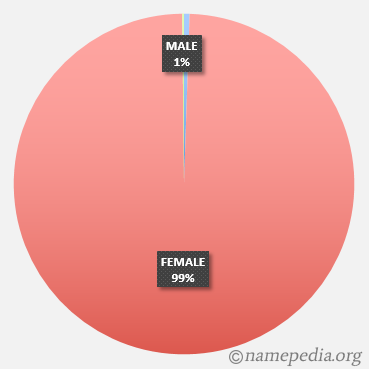

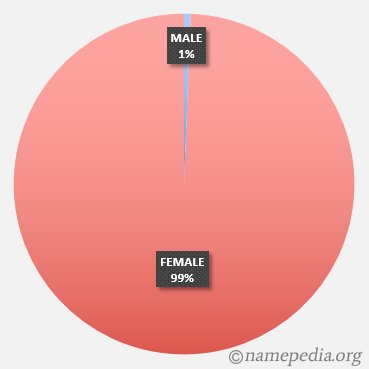

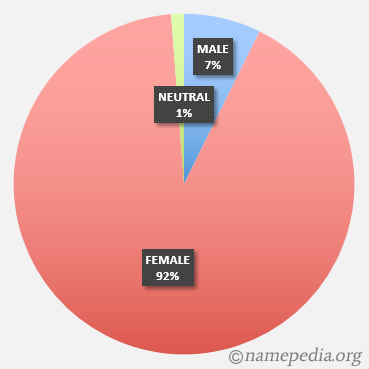

Female: 2127 (99%)

Neutral: 5 (0%)

*Includes names ending in а and я.

Biblical: 5

Diminutives and augumentatives: 74

Other: 75

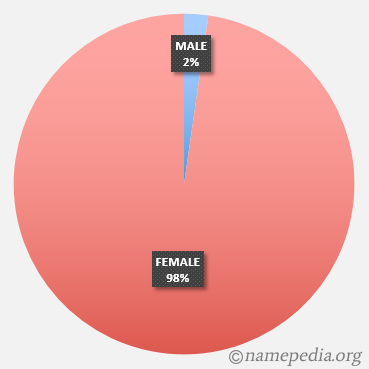

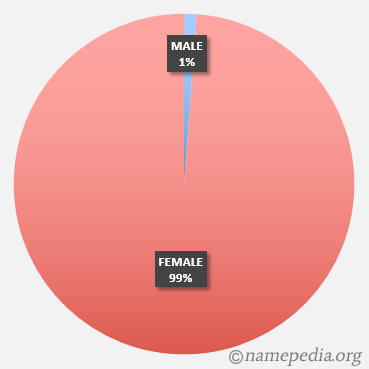

Feminine: 1152 (99%)

*Includes names ending in a and å.

**Nouns don’t have feminine and masculine gender.

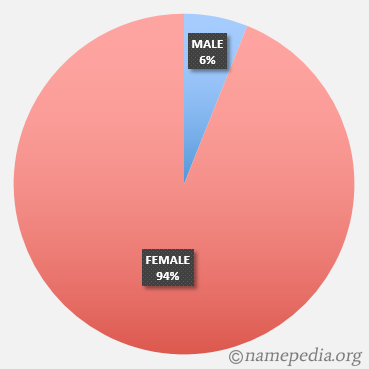

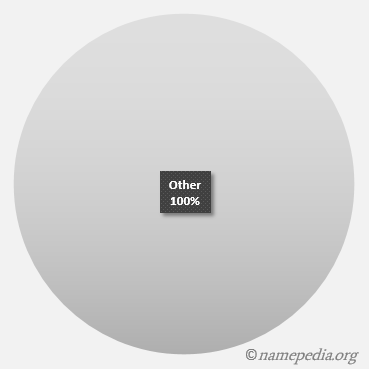

Feminine: 62 (94%)

*Nouns don’t have feminine and masculine gender.

Male names ending in “a” are an exception in most Indo-European languages, especially in those which have gender distinction in nouns. This article is meant to explain how they came to be and why.

Languages are like living creatures, always changing, always interconnected and names are no exception. We’ll have to wait and see what their next stage will bring!

Data sources:

• For the charts: http://namepedia.org